Angela Faris Belt is a fine art photographer, author and educator who engages other artists involved in creative photography with her writing. For her own photography, Angela uses a wide range of media to create conceptual images. I had the opportunity to chat with Angela about her series “Entropy”, which started as the result of having to salvage her work from a computer crash. The crash caused the scrambling a large number of her original digital photographs permanently, which she then proceeded to examine and curate for use in a show.

In a quick interview below, Angela answers eight questions about this series and her work in general. The work is currently on display starting tonight at the Dairy Center for the Arts in Boulder, Colorado and runs through August 2015.

Your “Entropy” series seems on the surface to be the glorification of, and finding the beauty in, the results of the critical malfunctioning of a system storing your raw vision. Is that how you’d describe it?

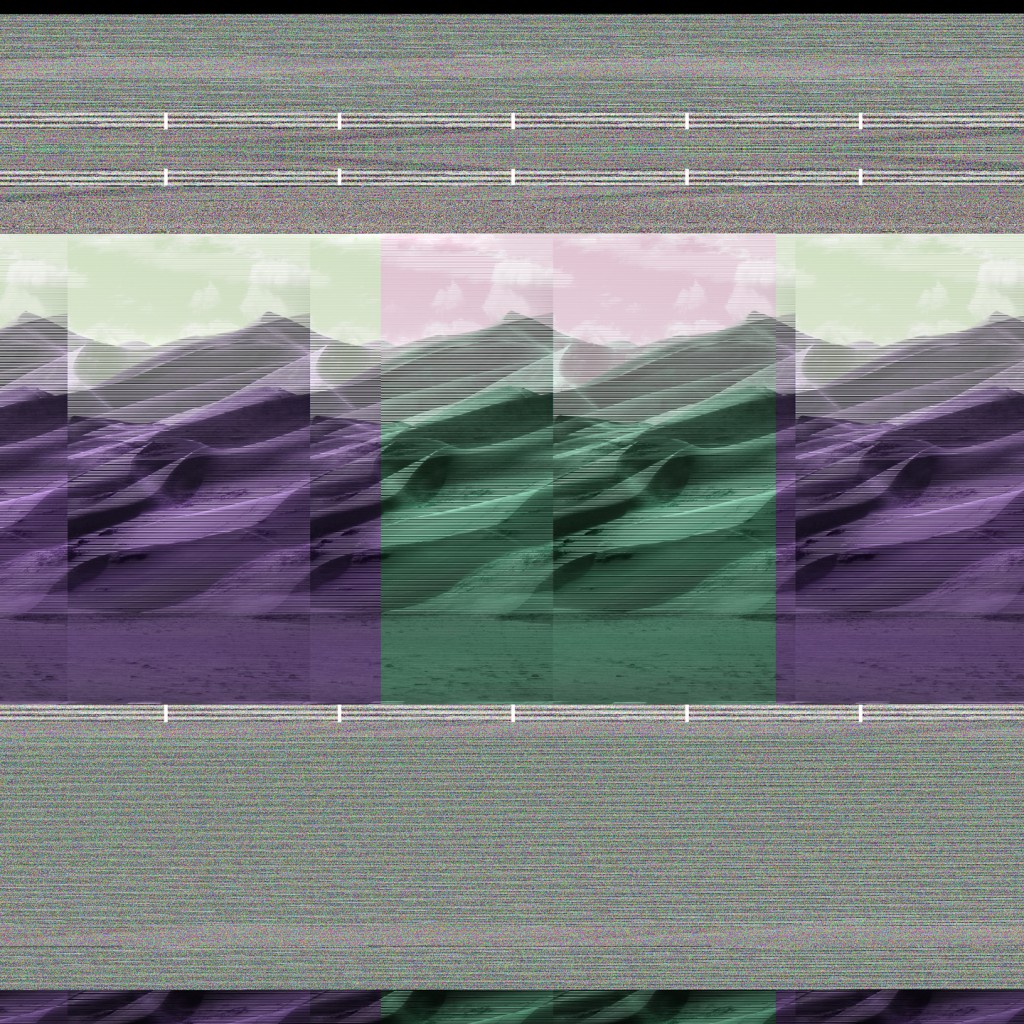

AFB: In many respects that’s right. My file system crashed while I was uploading images from a trip to the Great Sand Dunes. My hard drive was backed up, but that shoot was very important to me so I ran a recovery program to save it. Obviously the results weren’t as I’d hoped, and my first response was abject horror. But scrolling through the “recovered” files I realized something really unique and beautiful was happening, some kind of new landscapes that combined my own vision of the land with the digital language used to express it.

You’ve battled cancer and resulting physical difficulties for many years. Would you say this series is related to your body’s own malfunction and subsequent recovery?

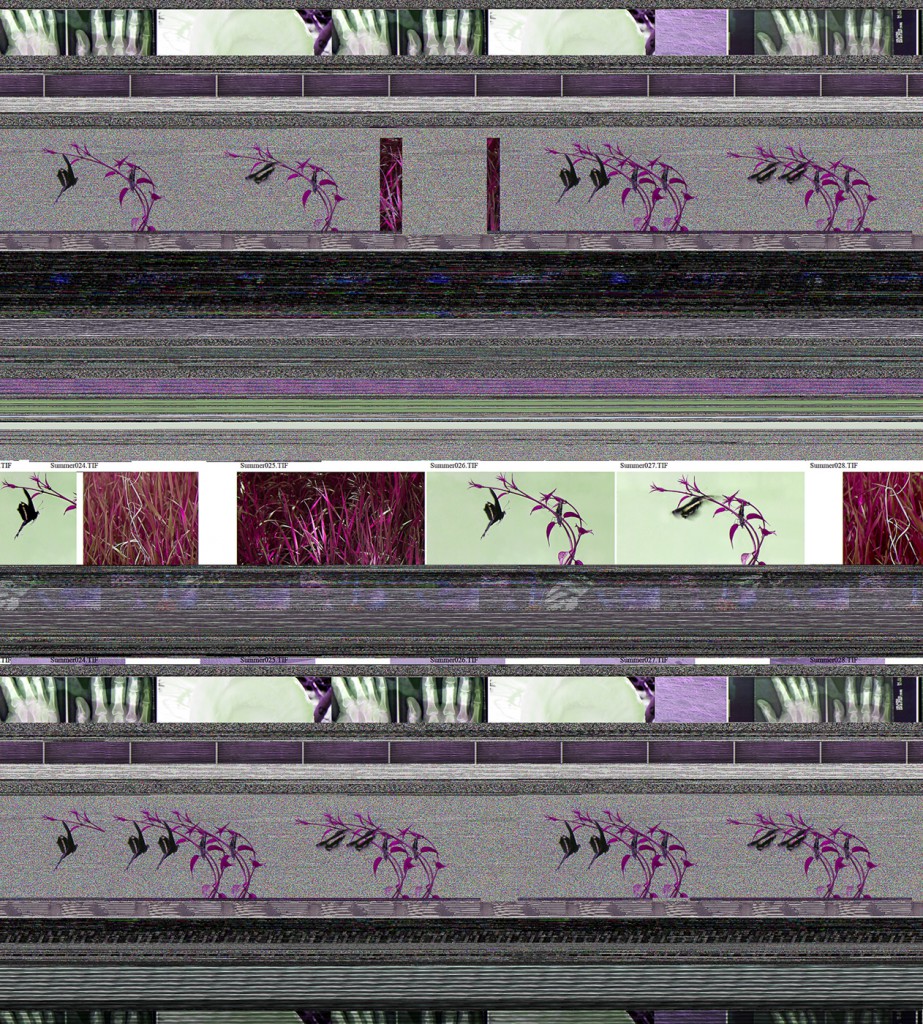

AFB: Wow, that’s the first time anyone’s made that connection. In fact I hadn’t even made it, so it definitely wasn’t conscious. But I do believe if you look closely at any artist’s work you’ll find parallels between its themes and the artist’s life experience. Our experiences form who we are; they influence our interests and guide our endeavors, so I think there is always an innate connection. In this case, disparate aspects of my life that I keep in discrete spaces on my hard drive became intermingled—my research and conceptual landscape images, contact sheets, demo images I use in teaching, and even personal snapshots and medical images like MRI’s and CT scans I’d saved. So the connection you mention between bodily and computer malfunction does emerge in several of the images, especially in the contact-sheet-looking images where the “inner workings” of a physical self juxtapose with the landscape.

Philosophically, I don’t really see the malfunction of a system (whether physical or digital) as wholly negative though; it’s part of the nature of things, and as such it helps to define the system of which it’s a part. Things we typically perceive as “mal-functioning” are at the same time “functioning” on some other level—even when we don’t like or understand it. That’s part of what worked for me in the recovered files.

Many of the pieces you selected seem to be of nature, but fragmented with repeating geometry characteristic of the digital world: static noise patterns, bifurcating triangles, and long horizontal lines segmenting your images and fractured iterations of your original photographs. What purpose does repetition of form serve in this series and art in general?

AFB: A vast majority of the recovered files were a cacophony of static or repeated patterns with nothing else going on—no meaningful content whatsoever. But when that randomized data was interspersed with some recognizable content, the result offered up a bizarre sort of symmetry that held potential meaning. The repeated and mirrored content in many of the images made me think about how so many of our images of nature are variations on a theme. That is, if we follow a formula for making a good picture of, say, a waterfall, we can then make a good picture of any waterfall. In that way these images are essentially interchangeable. Almost anyone can envision it, because you’ve seen it a thousand times: cascading water + pristine land on each side + camera on a tripod + long shutter speed = pretty waterfall picture. The formula developed because it works to meet our expectations—our ideal of how a waterfall should look. But those pictures usually have nothing to do with the specific waterfall imaged, which further underscores our homogenized beliefs about waterfalls (or any type of landscape image).

Some of the images resemble contact sheets often used to proof a series of photos back when we shot film instead of digital. In spite of the avant-garde/techno feel of some of these images, there is a definite sense of your experience in traditional photography and attention to detail as well. What do you believe some of these compositions you’ve chosen from your recovered hard drive say about your relationship to photography as a whole?

AFB: I’m part of the last generation of “born and bred” darkroom photographers who in graduate school began staring down the barrel of the digital photography age, and I for one wasn’t about to go willingly. During a conversation about it, my mentor, artist Joseph Grigely said, “Artists can’t be dependent on any particular medium or technology to make art.” I always remembered that, even though I thought I’d never adopt digital media. But years later as issues with my health developed, spending hours amidst darkroom chemistry aggravated them, and that sort-of forced my hand. So one day I got up, sold all of my camera and darkroom equipment, bought a digital camera and Photoshop, and never looked back.

I do think the influence of traditional darkroom practices is present many of these images, because that’s the tradition I came from and many of my digital working methods are a holdover. I champion the necessity of contact sheets, as my students can attest (or should I say protest). They allow us to look at the cumulative result of our work in a comparative space, to spend time going back and forth among several images. So even though I work digitally I still print contact sheets of my best images to use as an editing tool, and some of the images in Entropy that I found most interesting contain some of those elements—text, evenly spaced similar images, etc. In those images things that were once tangential—like file names and the variety of images on a single page—took on meaning. When you look at contact sheets you don’t think of them in terms of cumulative meaning…they’re just the best means of spending time with one’s work and deciphering what works within the context of all the images made.

I like the fact that even if the medium an artist uses isn’t intended to contribute to the work’s meaning, traces of it are always there. These contact-sheet-style images bring different aspects of that to the forefront. I intentionally chose files where the images they contained suggested meanings that would otherwise never be alluded to when seen in isolation or when viewing them as a contact sheet in the editing process.

You started this project with the goal of salvaging your work, but eventually gave in to accepting the random changes the recovery program and/or data corruption introduced. This formed a new context for your decision-making, and one could only assume, changed which images you chose to present. Some might call this the result of “happy accidents” or gifts from the universe. Is that how you see it?

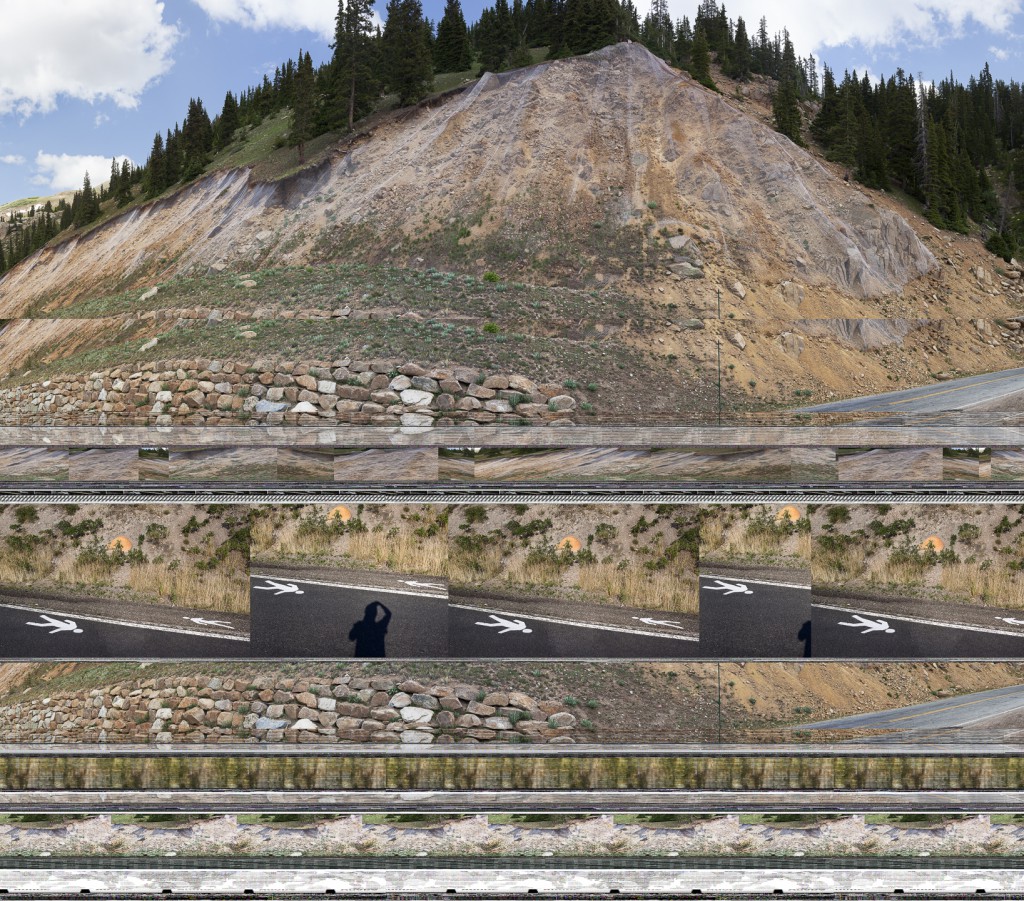

AFB: Well, the crash didn’t prevent me from printing and exhibiting any of my fine art images, since everything was backed up (with the exception of the Great Sand Dunes shoot, which only exists sporadically throughout Entropy). But the recovery program opened a window for the “ghost in the machine” to show itself, I responded to that. The whole thing reflects the lack of control we have over even the things we perceive as foregone conclusions. I suppose another bright side is that it allowed me to introduce some pretty landscape snapshots (my photographic guilty pleasure) because they were re-contextualized in conceptually interesting ways.

I love things like that—serendipity, happy accidents, random acts of kindness, and gifts from the Universe. Nature writer Annie Dillard says, “Beauty and grace are performed whether or not we will or sense them. The least we can do is try to be there.” Gifts are different than expectations. I like to think of the universe as showering us with gifts; they’re just hard to recognize when we’re so busy trying to open an umbrella! As I looked through the files I recognized literally each one of my photographs (and some from artist tear sheets and students’ projects, which I deliberately omitted), and I just had to let go of what I had intended for some of them and welcome the breadth and depth of new meaning derived from the resulting images.

Has having to evaluate your original photographs transmogrified by a random technical failure changed how you photograph subjects now? If so, how?

AFB: Oddly, no, but I think it’s because my work is always based on seeing something that’s already there, and translating it (using photographic language) for others to see and understand. In this case it’s changed my approach to making art in a broader sense by allowing me to examine the possibilities of using digital media itself to infuse meaning into the images. In the past I used historic/alternative photographic processes in my work, but when I switched to digital media I became rather photo-centric, meaning that I concentrated on the image as a singular construct. Now I’m beginning to experiment with layering images, and using Photoshop as a linguistic tool much as I would have used historic/alternative darkroom processes to add a “material” depth of meaning to the images. Nothing has come of this yet; I’m just experimenting with the tools.

The composition of photographs represents the state of mind of the photographer in many respects. Do the images you have chosen represent a mental state in general, or are they more of an intellectual statement than a visceral one?

AFB: For me art is always a balance of both; if it’s visceral enough it sparks something in my intellect as well. I sat this entire folder of recovered files aside for several years; I knew there was something there, but the timing wasn’t right because I was working on other things. But all the while the images were affecting me, because I never forgot them. I think I needed to wait until I found space to “edit from” rather then “create” new images in order to make good decisions about these files, and to cull an appropriate representation of images from the tens of thousands. I found hundreds of images that were visually lovely but had nothing to offer in terms of broadening or deepening the concepts emerging in the work, and I found hundreds of conceptually fascinating images that were a visual cacophony; both kinds of images were omitted from final body of work. It’s how I relate to any art. Take music for instance: if I heard about a new innovative kind of music, but it sounds atrocious, then I’d have a hard time caring what it might have to offer intellectually or to the world of music in general.

What would you like people to take away from this series of work?

AFB: For a time I lived just off the Blue Ridge Parkway in the North Carolina mountains. It was one of the most beautiful landscapes one could hope to live in, and I had a very nice neighbor not far away. Driving home early one particularly beautiful morning I saw her outside and I exclaimed, “Did you see that glorious sunrise?!” She responded, “Oh, you get used to it.” At that moment, I had heartfelt sympathy for her, and since then I realized that most of us grow numb even to the most spectacular landscape or natural event. We allow our perceptions to become too blunt to see the sublime in the familiar. It’s a shame, really, since the beauty we most often encounter is entwined in our everyday experience. Since that time I’ve referred to that kind of thinking as a kind of “poverty of spirit” that I consciously work never to succumb to.

I suppose I’d like people to think about the images they see, and to allow them to deepen their perceptions of their “everyday” landscape. I’d like people to recognize that the natural world is comprised of uniqueness rather than ubiquity, and that a generic photograph of a sunset is as limiting to our perception of an individual sunset’s transformative power as describing it with the simple word “sunset”. I also want the images to touch people as lovely landscapes in their own right, and remind them that through serendipity we can see the mystery underlying all things revealed.

Work from fine art photographer Angela Faris Belt‘s series “Entropy” is on display starting tonight at the Dairy Center for the Arts in Boulder. The show runs through August. Contact The Dairy for hours and directions.